Virtual and augmented reality: rethinking design in limitless spaces.

The same inherent qualities of augmented and virtual reality that mesmerize users also create unique challenges for designers and developers. Kenneth Woodruff, lifelong tinkerer, designer/developer and owner of Grand Unified LLC, outlines the difficulties of building AR/VR experiences and highlights some projects that are breaking new ground in the space.

It has been said that early moviegoers were so overtaken by the sight of a train steaming towards them on the screen that they jumped from their seats, screaming and running for the door. Though this tale is a myth, it embodies the leap that virtual and augmented reality present to us today. Even considering the current state of VR hardware, I have personally witnessed similar reactions from people trying it for the first time—mouths open in wonder, hands swinging controllers around like a child in a sea of fireflies for the first time. As with the advent of film, which added the dimension of time to our experiences, we are in the midst of shifting our experiences into a whole new dimension—that of space.

This isn’t the first attempt. Back in the 80s, we had Nintendo’s Virtual Boy. In the 90s, we had Lawnmower Man. The aughts were full of attempts at consumer, realtime 3D that never panned out. The present is something different. This is the first time we can enter alternate realities at home—on the couch, for fun, for information, for the sake of raw experience. We can live through augmentation on the same devices with which we make phone calls. Some of us hobbled through the previous waves with interest and hope, and learned lessons about limitations that have not really been solved, only updated.

I have recently found myself encountering some familiar issues in my work. The specter of visual design in this new dimension continually asserts itself. Elements that are designed in traditional ways, in 2D, and with the best intentions, often fall flat in this new space. Designers and developers have to completely rethink how to present information in the experience, because the old ways are suddenly quaint, boring, or literally nausea-inducing.

New medium, same challenges

Imagine the impact of the transition from mono audio production and consumption into the magical world of stereo. New equipment, new processes, new ways of thinking, and new techniques had to be developed. In a chicken-and-egg scenario, the new thinking and new stuff had to be sold to consumers to kickstart better ways and means, and convince producers that this was The New Way. It’s all so familiar.

For producers of AR/VR, one particular sticking point is the presentation of information—how to “physically” show the user/player/viewer what needs to be seen. Traditionally, some sort of HUD (heads up display) or constantly on-screen mechanism would show scores, health, a map, etc. In this new space with real depth, we can’t float elements in space in front of the user’s face without forcing them to refocus their eyes in order to see it. We can’t leave information floating a few inches in front of their eyes because this can lead to nausea—and actual eye-crossing. In order to overcome these issues, VR designers have to consider everything in their artificial world to be physical objects in space in front of you.

Space to rethink the user interface

At this stage in the development of the industry, the best way for a team to attack these issues is through research. Sampling the wide range of games and other experiences that are available on the market already will reveal some very clever solutions. Take the example of Vanishing Realms by Indimo Labs. The entirety of the traditional HUD is arranged around the player’s waist, which means it is only seen when looking down. This helps with immersion, and reaching for one’s waist to affect inventory allows for a much more visceral experience. Google’s Tilt Brush is an excellent example of diegesis—when an experience’s interface is right in the world. You paint with your hands, and your interface is your hands. It’s an extremely capable application, with many options available for immediate use without much fuss. Some designers may approach working in these new spaces as simply working with the same tools and methods that we have used for decades in 2D, while adding a little depth for flavor, but that comes across as just what it sounds like.

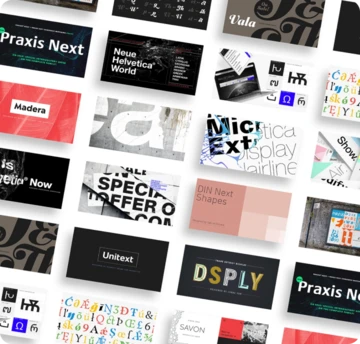

Another big issue is in presenting type. Type in realtime 3D has generally required bitmaps at large sizes for clarity, compromises in quality, or grainy-edged geometry that is difficult to read on smaller devices. We’ve lived without decent tracking, kerning, styling and other aids to clarity and legibility for years—mostly because software developers have put it on the back burner. Though it is essential for almost everything we do, text has never been at the forefront of realtime—or rendered—3D development. The focus has been on geometry, texturing, lighting, shadows, surfacing. Things are finally changing on that front.

Different realities require different treatments

Here we should draw a distinction between design and presentation in augmented reality vs. virtual reality. In VR, we are completely replacing the real world, and objects in that new world are intended to feel tangible, if not realistic. Even stylized productions like I Expect You to Die have a strong sense of presence. Text is in the world, or out of the way. Design elements are floated in such a way that they look manipulable.

The crux of augmented reality experiences is that you are doing something right there on your coffee table, without some isolating hardware strapped to your face. This kind of design is a bit more like… Fight Club. We label real things, add overlays, give the user/player information, objects and tasks that they would not normally have access to. Design-wise, text in particular is simpler, flatter, cleaner, more easily accessible.

These two avenues present different challenges, and different solutions.

VR’s double-edged sword

As with any technology, there are performance limitations. Even the highest-end hardware can’t draw at nearly the quality we have become accustomed to with “traditional” systems. Since the hardware has to draw 2 outputs at once, one for each eye, resolution and quality are limited. Compounding this horsepower problem is the need to draw at a much higher frame rate in order to reduce motion-related nausea. It’s quite a balancing act.

The irony in this is best described with an example. While walking around at a recent game developer conference, which was totally overtaken by VR games and technology, I remarked that everything in the preview monitors looked like something from the early 2000s. Geometry was simpler, textures were fuzzier, detail was low, all in an effort to keep the frame rate up. It was as if I were a time traveler, at a conference 10 years ago. You might have noticed this in screenshots or video clips of VR games, thinking they’re a bit more sophomoric than you’re accustomed to. The key is to remember that onlookers see something entirely different from the person wearing the HMD (head-mounted device). The very nature of seeing something in stereo creates immersion, and you quickly forget what is going on in the room around you, the resolution of textures, and that the shadows aren’t perfect. All of that criticism goes away when a horde of zombies is trying to eat your face and you are out of ammo.